Vaccine hesitancy is not uncommon in rural America. But the healthcare industry can’t forget about rural communities.

By Nan Sloan, Vice President of Compliance, Medecision

Last July, I published a blog post about COVID-19 and rural communities, and I shared how many people in rural areas feel immune to the coronavirus and its devastating effects. However, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), rural communities face unique challenges related to COVID-19. With more than 120 rural hospitals closing over the past decade, there are fewer hospital beds per capita and medical workforce shortages. People in rural communities are often at an elevated risk for COVID-19 related deaths due to age or chronic disease prevalence.

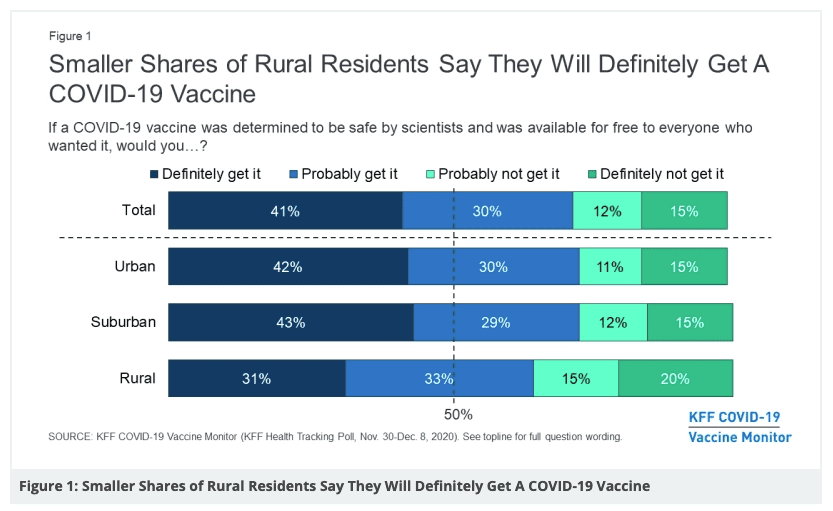

These realities are concerning—but even more so now because recent research shows that rural residents are among the most vaccine-hesitant groups. Individuals living in rural America are significantly less likely to get a COVID-19 vaccine, according to the KFF.

Even for residents in rural communities who do want the COVID-19 vaccine, getting one can be difficult. Despite an increase in COVID-19 vaccine distribution—and President Biden’s declaration that every American adult will be eligible by May 1—there are many obstacles to administering vaccines in rural areas. Challenges include:

- Lack of transportation. In densely populated urban areas with public transit, it’s easy for people to get to vaccination distribution sites. But people in rural areas might have to travel a long distance to get to their vaccination site—and may not have the transportation to do so. This can be even more challenging for people who receive the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines, which require two doses weeks apart. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released an encouraging report, however, stating that even one dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines is up to 80% effective. This is good news—especially for people in rural communities who may not be able to find transportation to get their second dose. (In late February, the Food and Drug Administration approved the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine for emergency use.)

- Lack of technology. Most vaccine appointments must be made online in advance. But for people who don’t have internet access or technology equipment (e.g., smartphones or computers), booking an appointment can pose a challenge.

- Misinformation and distrust. There is an abundance of misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccines—and the education about the vaccines provided to rural America is not the same as what’s given to people in metro areas. Furthermore, people of color often distrust the healthcare system because of a long history of racial disparities in the healthcare industry. Political beliefs also play a role, as many people in rural communities believe the government has exaggerated the coronavirus and its severity.

- Hard-to-reach populations. Just as in metropolitan areas, there are hard-to-reach populations in rural areas as well. Non-English-speaking, homeless or undocumented groups of people will need community-based organizations to reach out to them to discuss vaccinations.

Nonetheless, many healthcare and community organizations are taking measures to provide COVID-19 vaccinations in rural areas. For example, Prisma Health in Greenville, South Carolina, created mobile vaccination units and partnered with community organizations to reach rural and underserved communities. The vehicles, staffed with medical professionals, traveled to targeted areas to distribute vaccines to eligible members of the community. Community partners helped spread the word about the mobile vaccine clinics, even helping residents make appointments.

Another example is Lutcher, Louisiana, a parish of almost 3,200 people—about 49% of whom are Black. Staff at St. James Parish Hospital quickly noticed that the majority of people choosing to get vaccinated after seeing the hospital’s online and social media advertising were white. Hospital staff partnered with Black preachers and other local leaders to create a phone campaign to spread the word about vaccinations. The week after the phone outreach, vaccination among Black community members increased from 9% to 30%.

In Dalhart, Texas, a town with a population of about 7,000 people, a team of medical professionals and volunteer police officers and firefighters turned the town’s event space into a makeshift vaccine clinic. Senior citizens and essential workers were given priority, and ultimately 1,232 doses of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine were distributed. Nursing student volunteers were also on hand, offering to take photographs with props for those who wanted to send a photo to friends or family members or to post on social media—thus encouraging others to get vaccinated as well.

As COVID-19 vaccines become more readily available, it’s critical that the healthcare industry doesn’t forget our rural neighbors—and that we do everything possible to make vaccines easily accessible while also providing high-quality education about them.

About The Author: Nan Sloan

Nannette (Nan) Sloan is the Vice President of Compliance at Medecision. She has over 20 years of experience in healthcare regulatory and compliance; creating and delivering EHR, laboratory, process optimization, and payer case management solutions for clients; and leveraging her extensive background leading strategy and business development. Nan has cultivated a record of success for implementing solutions to track regulatory requirements, certifying products in alignment with regulatory requirements, delivering regulatory and compliance internal education certification plans, implementing corporate compliance plans, managing high-level client relationships, and driving corporate change for large, diverse organizations.

More posts by Nan Sloan