We saw a housing crisis in America this past year—and we quickly learned how important safe housing is to healthcare.

By Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

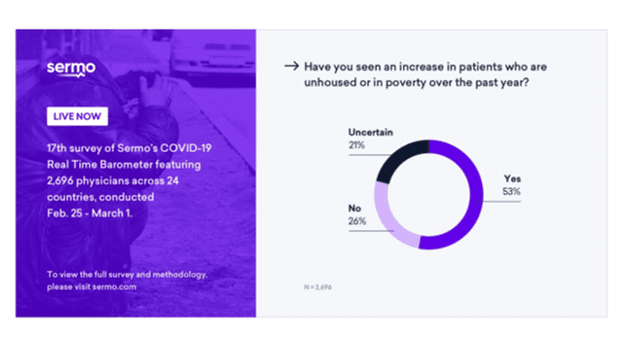

More than half of American physicians saw an increase in patients who lost their housing or fell into poverty over the past year, according to a February 2021 COVID-19 poll from Sermo.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, homes have been safe havens for people to shelter from exposure to the coronavirus. Housing is obviously the first and most basic need for people. It’s also a major risk factor for poor mental and physical health.

The Sermo poll also asked doctors about the biggest health issues associated with the impending housing crisis throughout the country. More than 50% of physicians cited mental health issues and depression; an increase of substance use; an increased strain on the healthcare system due to medical emergencies, malnutrition and food insecurity; and violence as the top factors.

Housing is getting needed attention from the healthcare sector a year into the pandemic.

Housing as a Social Determinant of Health

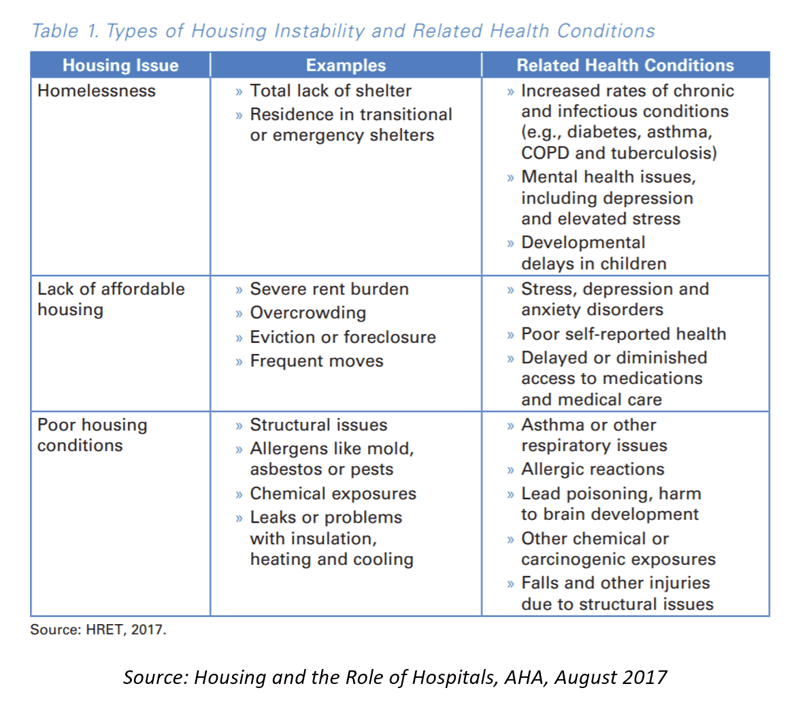

In a 2017 report, the American Hospital Association (AHA) focused on the hospital’s role in housing. This chart from the report describes housing issues and related health conditions.

The AHA’s report talked about “the web of housing and health,” noting that housing instability is not “randomly distributed.” As I’ve come to realize, risks of social determinants of health tend to travel in groups. For example, if a person is at risk of housing insecurity, then other risk factors such as nutrition, lack of transportation, lack of social supports, and/or lack of health insurance are likely to be present.

This is a “web” in that the factors contribute to and stem from each, as the table describes.

For example, consider the lack of affordable housing and related health conditions stemming from that issue: stress, depression, and anxiety; poor self-reported health; and delayed access to medical care and prescription drugs.

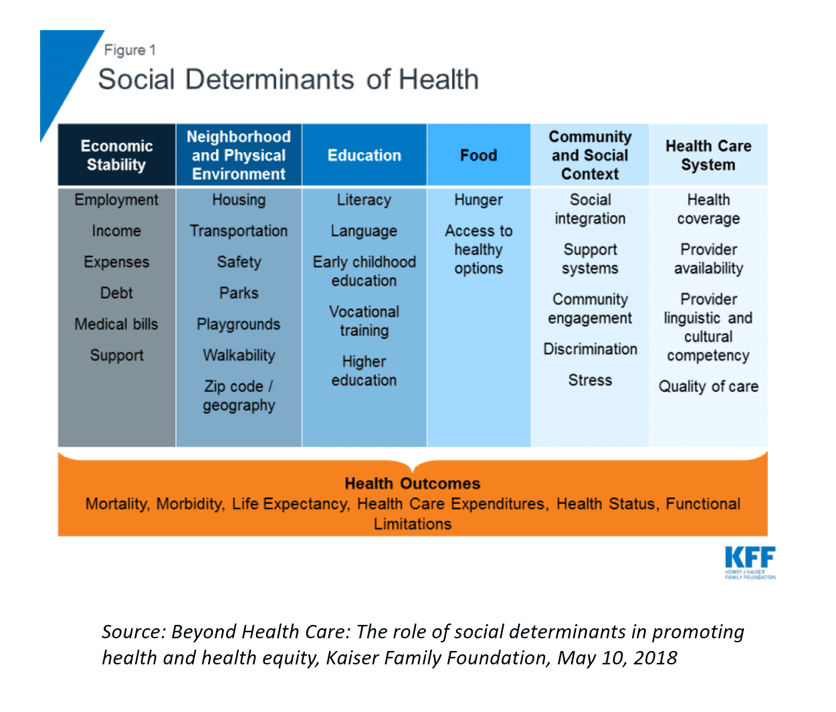

Above, the Kaiser Family Foundation details six categories of social determinants, which interrelate with housing (one of the neighborhoods and physical environment issues) and put people at-risk for various health outcomes.

COVID-19 Revealed Weaknesses in Affordable Housing

Within a few months of the pandemic emerging in the U.S., Brookings Institution pointed to a worsening housing crisis in America. In the U.S., renters historically have greater challenges finding affordable housing, and they were particularly hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brookings estimated that low- and moderate-income (LMI) households, which represent about 60% of the U.S. population, can spend more than half of their income on housing.

COVID-19 Worsened the Situation for LMI Families

At the beginning of 2020, there was already a shortage of affordable housing in the U.S., accompanied by increasing wage disparities.

AHIP, the health plan association, called out how COVID-19 exposed housing insecurity in a report published in January 2021. “Although low-income renters [have] demonstrated resiliency, they never achieved recovery from the housing crisis in 2010,” AHIP observed. “Instead, millions of Americans accepted evictions and utility debt as a means to survive.”

“Suddenly, every crack in the affordable housing continuum was exposed,” AHIP said.

And among the most exposed? Frontline, essential workers, according to a study from the Urban Land Institute’s (ULI) Terwilliger Center for Housing.

ULI studied real estate markets across the U.S., identifying severe cost burdens for housing in the most populous American communities. Across the nation, there is a lack of attainable homes especially for “critical members of the workforce,” ULI found in the 2021 Home Attainability Index. ULI’s occupational analysis looked at jobs along with housing prices by markets.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, ULI identified 12 highly impacted occupations with heightened housing-finance risks: healthcare workers, frontline workers and workers with elevated risk of income disruption.

Only three occupations earning median wages could afford to rent a “modest, two-bedroom apartment” in half of the regions studied: a geriatric nurse, cardiac technicians and long-haul delivery truck drivers.

The Role for Healthcare Organizations in Housing

“Health providers are realizing they can no longer expect to heal patients through medical treatments alone,” the AHA report on housing and hospitals asserted, “The economic benefits for hospitals can be significant … reducing homelessness and other forms of housing instability—through case management, supporting housing, housing subsidies or neighborhood revitalization—improved health outcomes, connects individuals with primary care, and reduces high levels of utilization.”

In addition to hospitals’ opportunity to address housing in their communities, other segments of the healthcare industry are engaging in housing-for-health. CVS announced a project of close to $600 million to expand housing, address social determinants of health and civil rights issues, in their words, to “address racial inequity and social determinants of health” in Black communities. In 2020, CVS invested more than $114 million in affordable housing to cover 2,800 units in 30 cities across 12 states.

Since 2011, UnitedHealth Group has invested over $500 million in affordable housing initiatives. The company’s investments focus on affordable housing for people struggling with homelessness, people living with disabilities, and those with greatest need such as seniors and veterans.

In addition to housing units, UnitedHealth’s program also includes on-site services for medical care, social and support, job training, childcare, computer labs, and playgrounds. The company’s housing investments span eighteen U.S. states.

Most recently, in January 2021, UnitedHealth Group finalized plans for a mixed-use housing development in Chicago. UnitedHealth Group collaborated with The Community Builders (TCB) and the National Affordable Housing Trust to invest in a model TCB calls “Community Life,” embedding six missions: workforce development, asset building, community engagement, youth development, education, and health and wellness.

The location is also on a bus route, six blocks from a train station and a highway— reinforcing another social determinant of health, transportation.

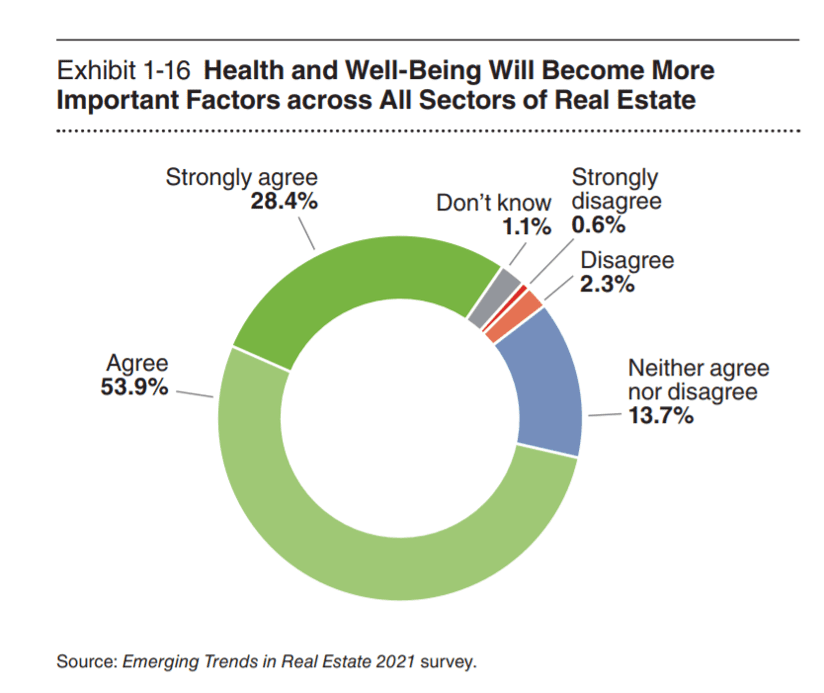

Then there is the real estate sector itself, which is morphing over into health and wellness, a trend accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic. Health and wellness have gained the real estate industry’s greater attention due to COVID-19, learned in a 2021 study by the Urban Land Institute and PwC.

For example, Communidad Partners may be a for-profit real estate company, but it is quite mission driven. They are collaborating with a national telehealth company to embed virtual care in their multifamily communities to mitigate against health care risks.

Working with Veritas Impact Partners, a non-profit organization, this could be the first real estate program to incorporate a telehealth contract with an un-named “Fortune 500 health care provider,” according to the company.

Communidad Partners focuses on under-served markets in the U.S. and has an explicit commitment to ESG principles—environmental, social, and governance.

The company’s managing partner Antonio Marquez said, “We’re always focused on health and wellness, but in the wake of COVID-19, the health and wellness that we would do before, which is focused on diabetes testing, we do dental checkups for kids—this is all in-person, human interaction, and we could no longer do that. … We needed to pivot and find a virtual way to engage with residents to fulfill our mission of health and wellness.”

Marquez’s goal is to get telehealth linked up with every resident in all of the company’s properties, ultimately reaching 20,000 households and 60,000 residents over the next five years.

The Meaning and Power of “Home”

In the wake of the pandemic, researchers looked into how people felt about their homes as a result of being compelled to shelter-in-place across the U.S.

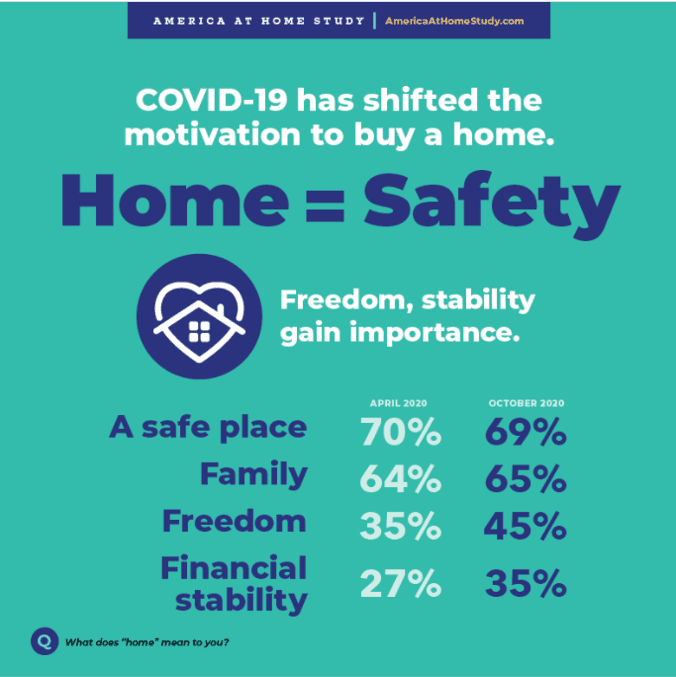

The America At Home study found the vast majority of consumers mostly thought about “safety,” followed by comfort and family.

There was a subtle shift in sentiment between April 2020 and the second wave of the study conducted in October: a growing motivation for “freedom,” among nearly one-half of Americans, and one-third looking for greater financial stability six months into their pandemic experience.

Safety, nonetheless, ranked first over time.

As the U.S. healthcare ecosystem considers life in America “after the pandemic,” whenever that “after” happens, it’s abundantly clear that “home” is not just a dwelling place, as our colleagues at Public Health England (the UK equivalent of the Centers for Disease Control) have observed.

Our homes “should be a place of comfort, shelter, safety and warmth … the main setting for our health throughout our lives,” Public Health England has said.

Housing is fundamental to health, requiring the corralling of resources in and beyond clinical care bundled with social services, housing (taking a page from Communidad Partners’ approach), and retail health.

COVID-19 has only exacerbated the challenge of unaffordable housing for health citizens in America. The time is perfect for public-private partnerships to address the web of challenges facing health citizens—especially those people on the front line of the coronavirus crisis.

About The Author: Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

Through the lens of a health economist, Jane defines health broadly, working with organizations at the intersection of consumers, technology, health and healthcare. For over two decades, Jane has advised every industry that touches health including providers, payers, technology, pharmaceutical and life science, consumer goods, food, foundations and public sector.

More posts by Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA